Herbal Remedies: A $4 Billion Enigma

APRIL 28, 2003

BUSINESSWEEK INVESTOR

| Herbal Remedies: A $4 Billion Enigma |

| Studies are only now looking into their safety and effectiveness |

Health-food stores, drugstores, and even supermarkets are stocked with

promises of a gentler, more natural kind of medicine. Echinacea extract labels

claim to boost the immune system. Gingko biloba promises to improve mental

sharpness. Ephedra is meant to supply energy and painless weight loss. Together,

these and hundreds of other herbal supplements amount to an estimated $4

billion-a-year industry that offers "health and longevity through the healing

power of nature," as a bottle of Nature's Way echinacea puts it.

But do these remedies work? And are they safe? The truth is, we don't have answers, since a 1994 law exempts the industry from the regulatory scrutiny the Food & Drug Administration applies to drugs. Studies have even shown that the ingredients in some herbal products change from batch to batch -- and the amount of active ingredients can vary depending on how and when an herb is grown. "In many ways, dietary supplements have aspects of a 'buyer beware' market," says FDA Commissioner Dr. Mark McClellan.

Because of the unknowns, people who use supplements could be risking harm, critics warn. They point to the Feb. 17 heatstroke death of Baltimore Orioles pitcher Steve Bechler, which they believe was at least partly caused by an ephedra supplement he took, as another sad reminder that natural doesn't necessarily mean safe. "Studies should be done first, rather than counting the bodies after," says Dr. Sidney Wolfe, director of Public Citizen's Health Research Group.

The encouraging news is that science is beginning to get some answers, thanks to studies funded by the National Institutes of Health on everything from St. John's Wort to saw palmetto. So far, the results show that most herbs tested do seem reasonably safe -- although they often have side effects such as headaches and diarrhea -- and a few, such as garlic and gingko biloba, may offer small benefits. But overall, researchers such as Dr. Stephen Bent of the University of California at San Francisco, who had hoped to find viable alternatives or adjuncts to mainstream medicine, have been disappointed. "Unfortunately, I've come to the realization that while there are some effective herbs, the majority probably don't work," Bent says. After all, he suggests, if herbs really delivered the promised benefits, drug companies would have already mined their active ingredients to create new medicines.

Consumers seem to be getting the message for some herbs. Last April, a team led by Dr. Jonathan Davidson of Duke University Medical Center reported that St. John's Wort didn't help in cases of major depression, even though previous studies suggested some benefit in milder depression. Meanwhile, other studies showed that taking the herb caused drugs such as AIDS medications to be less effective. Partly as a result of this new information, sales of St. John's Wort have plunged in the past year, according to the Natural Marketing Institute, a market research firm.

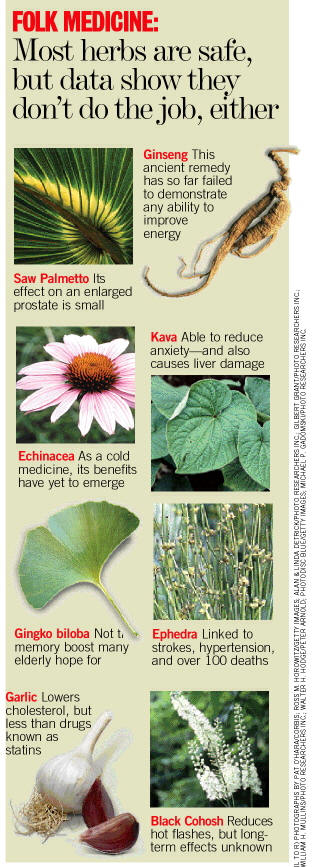

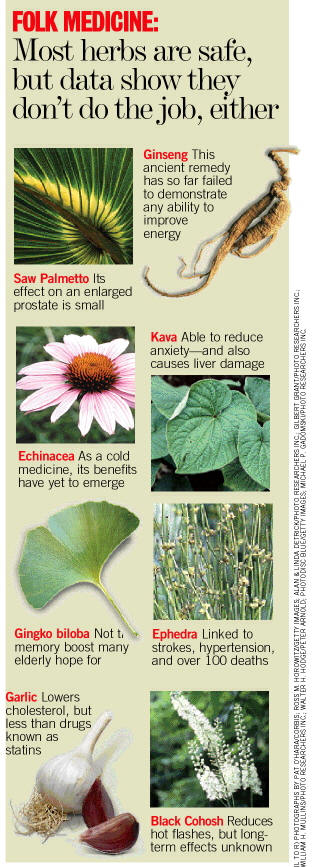

Other herbs are finding more takers. In the wake of studies questioning the benefit of hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal women, sales of a claimed natural alternative -- black cohosh -- are up. So what works and what doesn't? Here's a quick guide:

-- GARLIC. Taken in doses higher than you would get in food, garlic lowers cholesterol -- by about 4% to 6%. That's small in comparison with the more than 20% reduction from drugs called statins, so garlic is not a solution if you have a cholesterol problem, doctors advise.

-- SAW PALMETTO. As men age, many experience an enlargement of the prostate that slows the flow of urine. Some studies show that an extract from the berry of the saw palmetto plant appears to offer an improvement. The effect is small compared with that achieved by drugs for the same condition, but the herb may avoid the drugs' side effects.

-- GINGKO BILOBA. Long used in Chinese herbal medicine, gingko extracts are supposed to increase circulation and boost brain function. The evidence now suggests a small benefit for people with dementia, but other studies show no improvement in memory or thinking in the healthy elderly.

-- GINSENG. This root is an ancient remedy for everything from low energy and cancer to impotence. But research has yet to show any improvements in energy or other conditions.

-- ECHINACEA. Some studies have hinted that echinacea could slightly reduce the duration of colds -- but not prevent them. A recent large trial showed no effect. Dr. Ronald Turner of the University of Virginia is continuing to study the herb but doubts whether he'll find any benefits. "My interpretation of the scientific literature is that no data suggest that echinacea has any beneficial effect," he says.

-- BLACK COHOSH. Native Americans used the roots of this member of the buttercup family for everything from colds to malaria, and it became a home remedy for menstrual problems. Now, some studies indicate that the preparation reduces hot flashes and other symptoms of menopause, but researchers caution that long-term effects are unknown.

-- KAVA. Derived from the roots of a plant from regions of the Pacific, kava appears to have some effect in reducing anxiety. But it can also cause liver damage, which is why Canada and other countries have warned people not to use it.

-- EPHEDRA. This plant, also known as ma huang, contains compounds called ephedrines that are closely related to amphetamines. Studies show a modest weight-loss effect, but the supplement has also been linked to strokes, hypertension, heart problems, and more than 100 deaths. The industry claims it's safe when used as directed, but "everyone in the medical community knows ephedra can kill you," says Dr. Raymond Woosley, vice-president for health sciences at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. Indeed, ephedra appears to be at least 100 times as risky as any other herb. The medical community has asked the FDA to take ephedra off the market for years. Under the 1994 law, however, the agency must "scientifically" prove a product is unsafe -- a high standard of evidence. Still, says Health & Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson, "if NIH can establish ephedra is unsafe, I'm going to ban it."

On Mar. 7, the FDA proposed rules requiring dietary-supplement companies to follow so-called good manufacturing practices, ensuring that each product contains what the label claims. But it will be several years before the rules can go into effect. "Five years from now, you will see a more rigorously regulated industry," predicts a top FDA official. By then, studies now under way will have provided more definitive answers. For now, the promises on herbal supplements' labels are largely unproven.

By John Carey

About this site Copyright © 2024 - Kura Trading Company. All rights reserved. Comments? Suggestions? admin@kuratrading.comCopyright 2000-2003, by The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. All rights reserved.

Terms of Use

Privacy Policy